Independent pharmacies closing, leaving many in ‘drugstore deserts’

Published 10:45 am Wednesday, November 17, 2021

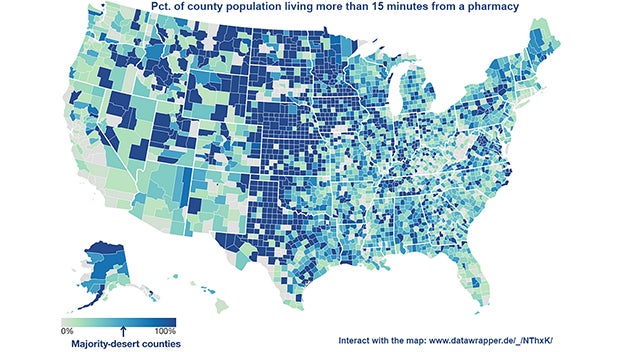

“Corner pharmacies, once widespread in large cities and rural hamlets alike, are disappearing from many areas of the country, leaving an estimated 41 million Americans in what are known as drugstore deserts, without easy access to pharmacies,” Markian Hawryluk reports for The Washington Post.

“An analysis by GoodRx, an online drug-price-comparison tool, found that 12 percent of Americans have to drive more than 15 minutes to reach the closest pharmacy or don’t have enough pharmacies nearby to meet demand. That includes majorities of people in more than 40 percent of counties.”

Independent pharmacies are struggling to compete with chains whose relationships with insurers and pharmaceutical benefit managers give them a competitive edge. “Insurers also have ratcheted down what they will pay for prescription drugs, squeezing margins to levels that pharmacists call unsustainable,” Hawryluk reports. “As the insurers’ drug plans steered patients to their affiliated drugstores, independent shops watched their customers drift away. They find themselves at the mercy of pharmaceutical middlemen, who claw back pharmacy revenue through retroactive fees and aggressive audits, leaving local pharmacists unsure if they’ll end the year in the black.”

In 2020, Kentucky lawmakers passed Senate Bill 50, sponsored by Sen. Max Wise, R-Campbellsville, to deal with some of these issues, which Kentucky pharmacists have long said are so bad they are putting some of the state’s drugstores out of business.

The law requires the state to hire a single pharmacy benefit manager to manage the $1.7 billion-a-year prescription drug business of Kentucky Medicaid, which covers about a third of the state’s population. It also established a single preferred drug list, or formulary, for all of the state’s Medicaid managed-care organizations and put the state Department for Medicaid Services in charge of the reimbursement methodologies, including dispensing fees.

Further, the law requires the PBM to pay the managed-care firm the actual discounted pharmacy price negotiated with the pharmacy network and prohibits spread pricing, in which a PBM keeps the difference between what it bills Medicaid for medications and what it pays the pharmacy to dispense the drug. It also prohibits a whole list of fees and prohibits PBMS from taking retaliatory actions against pharmacies, among other things.

A 2019 state analysis called “Opening the Black Box” found that the PBMs made $123 million through spread pricing.

Those pressures have whittled away at the number of independent pharmacies. “From 2003 to 2018, 1,231 of the nation’s 7,624 independent rural pharmacies closed, according to the University of Iowa’s Rural Policy Research Institute, leaving 630 communities with no independent or chain retail drugstore,” Hawryluk reports.